From long-lost shipwrecks to bizarre forms of life, Earth’s oceans are teeming with untold mysteries.

Yet despite decades of exploration, a study published in Science Advances has shown we still don’t know what is lurking in 99.999 per cent of the deep ocean.

Since 1958, 44,000 dives have only visually observed an area one-tenth the size of Belgium.

Scientists say this is equivalent to trying to learn about every ecosystem on land by looking at an area the size of Houston, Texas.

Now, an incredible interactive graphic reveals what lurks in this strange world beneath the waves.

Defined as being deeper than 200 metres (656ft), the deep ocean makes up 66 per cent of the surface of the planet.

However, researchers from Ocean Discovery League now say that our understanding of the ocean’s depths is woefully inadequate.

Dr Ian Miller, chief science and innovation officer at the National Geographic Society which provided funding for the study, says: ‘There is so much of our ocean that remains a mystery.’

As this interactive graphic shows, Earth’s oceans are divided by depth into different zones: the epipelagic, mesopelagic, bathypelagic, abyssopelagic, and hadalpelagic.

The epipelagic, also known as the sunlight zone, is the very top layer of the ocean where visible light can still be found.

Extending down to 200 metres (656 ft) below the surface, the epipelagic zone is home to many familiar species such as dolphins, sharks, turtles, and whales.

Photosynthesising plankton in this layer produce 50 per cent of the planet’s oxygen and are a key part of the ocean food chain.

However, despite this region being the main focus of human marine activity, it only makes up a small part of the total ocean.

In fact, 50 per cent of the planet is covered by ocean which is at least two miles (3.2 km) deep.

Just below the sunlight zone is the mesopelagic zone, also known as the twilight zone.

This region extends from 200m to 1,000m (3,280 ft) deep, where light cannot reach at all, and some studies suggest it might contain 10 times more biomass than the other ocean zones combined.

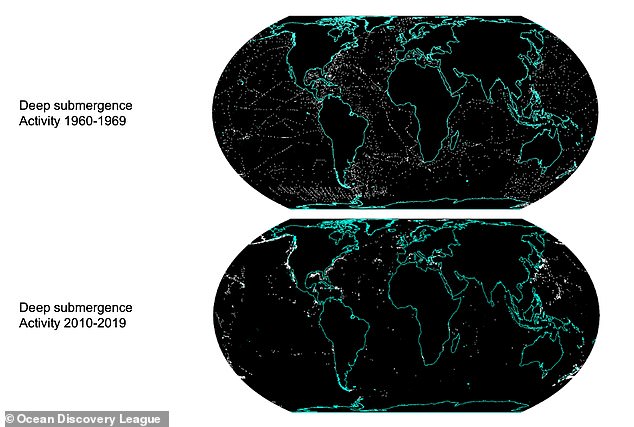

A new study shows that humans still have no idea what is hiding in 99.999 per cent of the deep ocean – defined as ocean deeper than 200m. This map shows areas where deep-sea dives have taken place since 1960

As this map shows, the area of deep ocean explored by humanity is tiny. In total, this makes up an area one-tenth the size of Belgium

In the total darkness and extreme pressures of the deep sea, only strange creatures like this Bigfin squid in the Gulf of Mexico are well adapted enough to survive

Researchers exploring the deep sea have already found bizarre forms of life, including a sea toad, flying spaghetti monsters (pictured), and a Casper octopus

However, scientists’ knowledge of what lies in these deep ocean zones is exceptionally slim.

Looking at recorded dives since 1958, the researchers found that humanity has visually observed an area of deep ocean no larger than Rhode Island.

Given that not all dives are public, the researchers say their figure is at the low end of estimates.

However, even if they were off by an order of magnitude, humanity still would have seen less than a hundredth of a per cent of the deep ocean.

To make matters worse, the recorded observations we do have are often low quality or inaccessible to the scientific community.

Almost 30 per cent of all documented observations were taken before 1980 and so only resulted in low-quality black and white images.

A large part of that imagery collected over the last seven decades is not accessible to scientists since it is either not digitised, still stuck on hard drives, or not catalogued.

Additionally, the researchers point out that humanity’s attempts to explore the deep oceans have focused heavily on just a handful of tiny areas.

Scientists have mainly focused their attention on features such as the Nazca Ridge, where they have uncovered a huge underwater mountain teeming with life. However, this leaves areas like the abyssal plains unexplored

97 per cent of deep-sea expeditions since the 1950s have been conducted by researchers from Germany, France, Japan, New Zealand, or the US

The records reveal that over 65 per cent of all observations have taken place within 200 nautical miles (370 km) of the US, Japan, or New Zealand.

Due to the extreme costs of ocean exploration, research teams from the US, Japan, New Zealand, France, and Germany were responsible for 97 per cent of all observations.

These expeditions have also tended to favour certain habitats such as ocean ridges and canyons, leaving the vast areas of the abyssal plains and seamounts unexplored.

This limited exploration means there is likely to be an incredible diversity of life that is totally missing from our understanding of the ocean.

For example, scientists discovered over 5,000 new species in just one underexplored zone.

The researchers point out that these little-known areas could provide the planet with climate regulation, a source of oxygen production, and even crucial pharmaceutical discoveries.

Just last year, scientists discovered that metals 3,900 metres (13,000 ft) below the surface produce ‘dark oxygen’.

This discovery challenged long-held assumptions that only photosynthetic organisms could produce oxygen and could call into question how life on Earth began.

With such a small region of the world’s oceans discovered, scientists only have a tiny amount of data to work with. This would be like trying to understand every ecosystem on land by looking at an area the size of Houston, Texas. Pictured: A heatmap of deep ocean exploration

Scientists are still learning more about the deep oceans and making new discoveries, such as the first live observation of the colossal squid, Mesonychoteuthis hamiltoni, in its natural habitat (pictured)

Metals on the deep-ocean floor produce ‘dark oxygen’ 3,900m (13,000 ft) below the surface, a new study has suggested. However, scientists still don’t know enough to understand how this could be affected by ocean mining

However, the scientists who made the discovery also warned that new deep-sea mining could disturb this poorly understood mechanism.

Without more knowledge of the underwater environment, scientists still don’t know exactly what impact this might have on the wider ecosystem.

Lead researcher Dr Katy Croff Bell, president of the Ocean Discovery League, says: ‘As we face accelerated threats to the deep ocean—from climate change to potential mining and resource exploitation—this limited exploration of such a vast region becomes a critical problem for both science and policy.

‘We need a much better understanding of the deep ocean’s ecosystems and processes to make informed decisions about resource management and conservation.’

This article was originally published by a www.dailymail.co.uk . Read the Original article here. .